How to publish a novel (when traditional book publishing is broken)

Should I self-publish my novel (how to publish a novel)

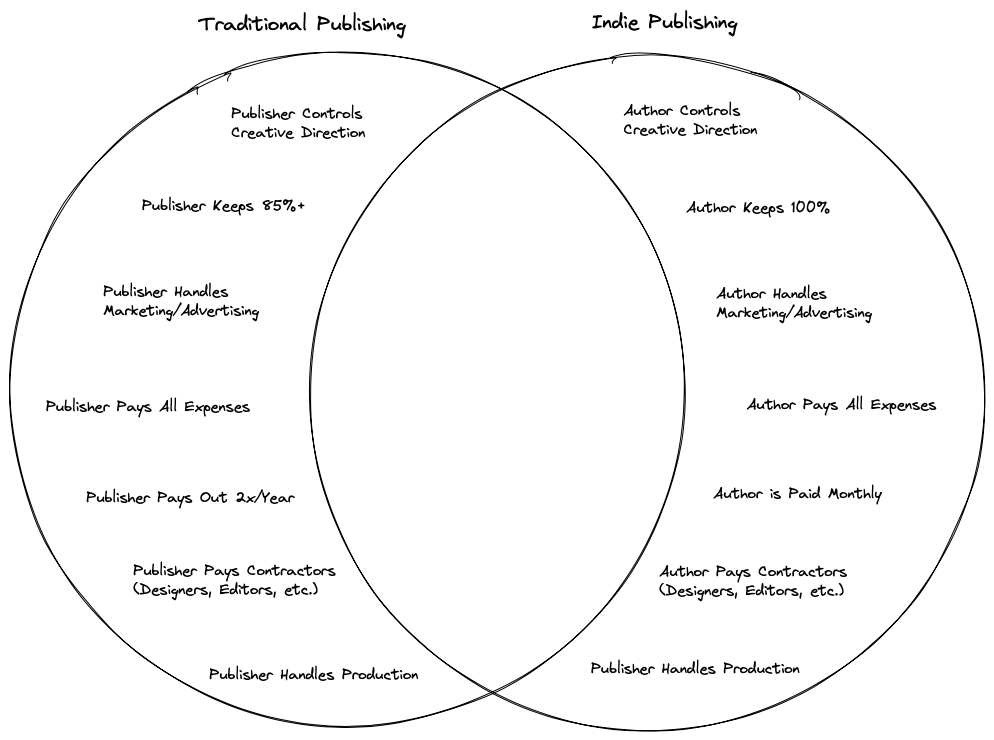

The decision to self-publish a novel is not an easy one. However, if you are thinking about it, you should consider that the choice is not necessarily between “choosing” one (self-publishing) over the other (traditional publishing), but choosing to release your book on your own, or attempting to land an agent, query publishers, and get past editing and gatekeeping.

Traditional publishing is broken… but it can be fixed.

I know, I know… with a title like that, you’d expect a good, long rant. Especially from a veteran indie author who has self-published over 50 titles.

And it’s true — I do think indie (or “self”) publishing is an amazing move toward bringing control and accessibility back into the hands of the creator, and a great way to remove the unnecessary gatekeepers of the industry.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no place for traditional publishing. In fact, you’re reading this post on the blog of a… wait for it… traditional publisher.

Traditional publishing vs. “indie” or self-publishing

So it’s probably a valuable first exercise to define what these words even mean. That’s easy enough, because I have my own definition (I own the company, so I’m allowed this small victory):

A traditional publisher is a company that publishes an author’s work, handles the details and creative direction, and bears all the costs.

Who pays for your help publishing a book?

An independent publisher or self-publisher is an individual that runs a team (or does everything on their own), and bears all the costs.

It’s a subtle difference, but I like to simplify it to: a traditional publisher pays for everything.

That’s it. If you (the author) are being asked to pay for anything by a publisher, that publisher is now either a hybrid publisher or a vanity press. Stay far away from the latter, be wary of the former. In fact, our friends at Reedsy have compiled a fantastic search tool for genre-based independent publishers that aren’t predatory or bait-and-switch operations.

The “traditional” publishing process

Most authors start their careers looking for an agent, querying editors and publishers, and receiving rejection after rejection until that sweet, sweet “yes” shows up. Some (read: most) never get it. Some get it, but then get locked into a low-paying, long-churn cycle of 18-month releases, poor-to-no editorial, and equally abysmal art direction.

Some authors smarten up at this point and ask themselves the fateful question: “What the hell is happening? Why can’t I do that myself?”

And the truth is… they usually can do it themselves. If they’re willing to part with a bit of cash, bring on a contracted designer or editor or two (or three), they absolutely can do it themselves. Add in a behemoth marketplace that allowed these self-produced titles to upload their books and sell them to the unassuming masses, and a new industry was born.

And that, in a nutshell, was the birth of the self-publishing age.

Is self-publishing better than traditional publishing (should you self-publish your book)?

This question is often the next thing out of someone’s mouth when I’m explaining the differences. In short, there are a tonof reasons why self-publishing is a great fit for most authors. It’s not perfect, but it’s got the most important two features going for it:

- It lets the author maintain full control over their work and property

- It lets the author retain the bulk of the royalties earned

Benefits of self-publishing your story

There are other benefits: speed, quality (if willing to invest, of course), iterative improvements, better reach, copyright exploitation, etc., but the two most important features of the indie world are the two listed above.

By contrast, most traditional publishers take 85% or more of the author’s royalties, and only pay out that piddly 15% afterthe author has “earned out” whatever measly advance they got. Further, the trad-pub shop will wrest control from the author’s white-knuckled fingers and claim to know things, like “what sells best,” “what designers like,” and “what’s trending.”

They’ll slap on a cover that might work, might not, but you’d better believe they won’t be changing that cover. Ever.

So, for a massive cost to the author (extremely low advances and royalties), they are locked into a term that can extend anywhere from 7 years to the lifetime of the copyright.

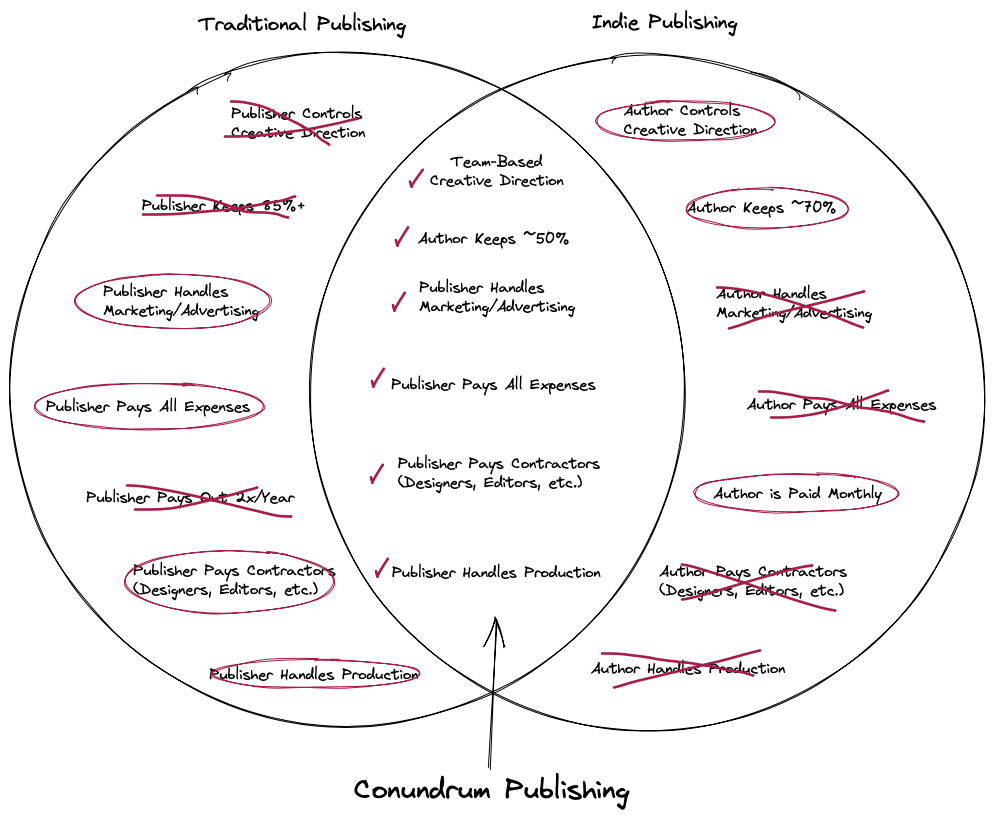

So how is Conundrum Publishing better, even if it’s a “traditional” publisher?

The natural question to ask is, “why is Conundrum Publishing — a traditional publishing company — bashing trad-pub?”

The answer is simple: traditional book publishing is broken.

It’s broken, but it doesn’t need to be. The issue with the traditional publishing model is that it’s outdated and dying, and no one seems to be doing a damn thing about it. Sure, there are cute little ebook stores popping up on the major houses’ websites, and some even — gasp! — have hired a “social media expert” to “brand” their “online interactions” (insert corporate synergy-speak here).

Publishing fiction books the “traditional” way doesn’t work to sell books (anymore)

No, really — when was the last time you went to Hachette’s website and bought a book from their hero graphic slider because “I love everything Hachette publishes!”?

When have you ever clicked a tweet from Penguin Random House and bought a book because you trusted Penguin Random House’s ability to know you as a consumer?

We don’t buy books from publishers. We buy books from authors.

We don’t buy books from publishers. We buy books from authors. We don’t shop at marketplaces. We try to discover the next great book for us.

Traditional publishing is too big, too broad, too out-of-focus, too boring. Indie publishing can bridge that gap, but often doesn’t — hordes of individual independent authors, all trying to push each other down so that their stuff gets pulled up.

Is there a place for traditional publishing in a world of self-published novels on Amazon?

But my belief is that there should be a place for traditional publishing: there should be a way for readers to connect with authors, on a platform that’s bigger than just one, but not so big that one gets lost in the fray. There should be publisher that actually, you know, cares about authors as much as they care about the readers.

And that’s where — if you’ll excuse a bit of “horn tooting” — Conundrum Publishing is changing the game.

Focus is key: authors win first.

First, we focus on thriller novels. That’s it. No fantasy, no science fiction, no romance. Sure, there might be elements of those in our thrillers, but we’re focusing on what we know, and we know thrillers.

Second, we believe that authors win first. Sure, we’re a business — we want to make a pile of money, grow, birth little baby Conundrum imprints, etc. But we can’t do that unless and until our authors win. If they’re not making money, we’re not making money. Simple as that.

What old-school traditional publishing really is

Third, we believe that traditional publishing (the old-school way) is really about stroking the egos of editorial staff, agents, and publishing execs. No one really cares if the author wins, because OMG we just turned down 13,000+ submissions last year because we are so exceptionally gifted at picking the best of the best. Never mind that of those rejected submissions, 37 were published across all genres, leaving readers scratching their heads as to why in the hell it’s taking so long to find another favorite author. New York and London (where English-speaking trad-pub lives) are about perception, not profit.

At Conundrum, we want to make sure there’s no losing sight of the simple fact that if we don’t sell books, no one wins. Not our authors, not our staff, and certainly not our readers.

The way forward is a new model of traditional publishing

So we do things differently… and it shows

Instead of a “slush pile” 14,000-plus titles deep, we want to see thrillers only, and we very likely won’t outright reject one — we’ll tell the author what they need to do get it in line with the market, to fit reader expectations, to craft the plot and narrative structure to fit genre tropes. That’s the beauty of being small: we can afford to do that, with each and every submission.

The process of writing and publishing needs a remodel…

Then, we send the book through our Roundtable — the first of its kind in the publishing industry. How does Pixar continue churning out blockbuster hit after blockbuster hit? They have a similar process called the Braintrust, where leaders in the company work with the director of a film to workshop a title before and during production. It’s not a “design by committee” situation, either — each of the folks on our Roundtable are expert thriller authors, and have the sales to back it up.

…And a new way to bring books to market.

After that process is finished and the rewrites are done, we’ll send the book through The Gauntlet, our AI-based, human-led editing suite. The best of machine-learning algorithmic prediction, fed a steady diet of thriller novels, accompanied by a pair of professional human eyeballs, whip the book into even better shape.

And we’re not even done. After The Gauntlet, the book is sent to our 200-person beta team, who squeeze every last typo out of the manuscript, leaving only beautiful, thrilling prose. The book has the absolute best chance of success it ever will have — especially compared to an independent author trying to do all of this themselves. It’s not impossible, but it’s incredibly difficult.

And yet… we’re still not done. All of that money we (Conundrum) saved not having to spend thousands to pay individual developmental editors, line editors, publishing executives, and agents, means we can put our money where our mouth is: we know how to advertise and market thrillers, and we will. Most publishers have absolutely no idea how to even start using a platform like AMS (Amazon Marketing Services) or Facebook Ads to sell books, but we do.

Traditional publishing doesn’t have to suck.

Traditional publishing isn’t inherently bad, it’s just that It is a dinosaur of a system — a true “old-school” model, funded by multinational conglomerates who want their finger in the literary pie. We’ve rethought what it means to be a publisher, and we think our model is not only here to stay — it’s going to be copied and emulated.

It’s already working, and we’re not even six months into it.

![What Just Happened? [Q1 Update]](https://www.conundrumpub.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/travel-landscape-22.jpg)

0 Comments